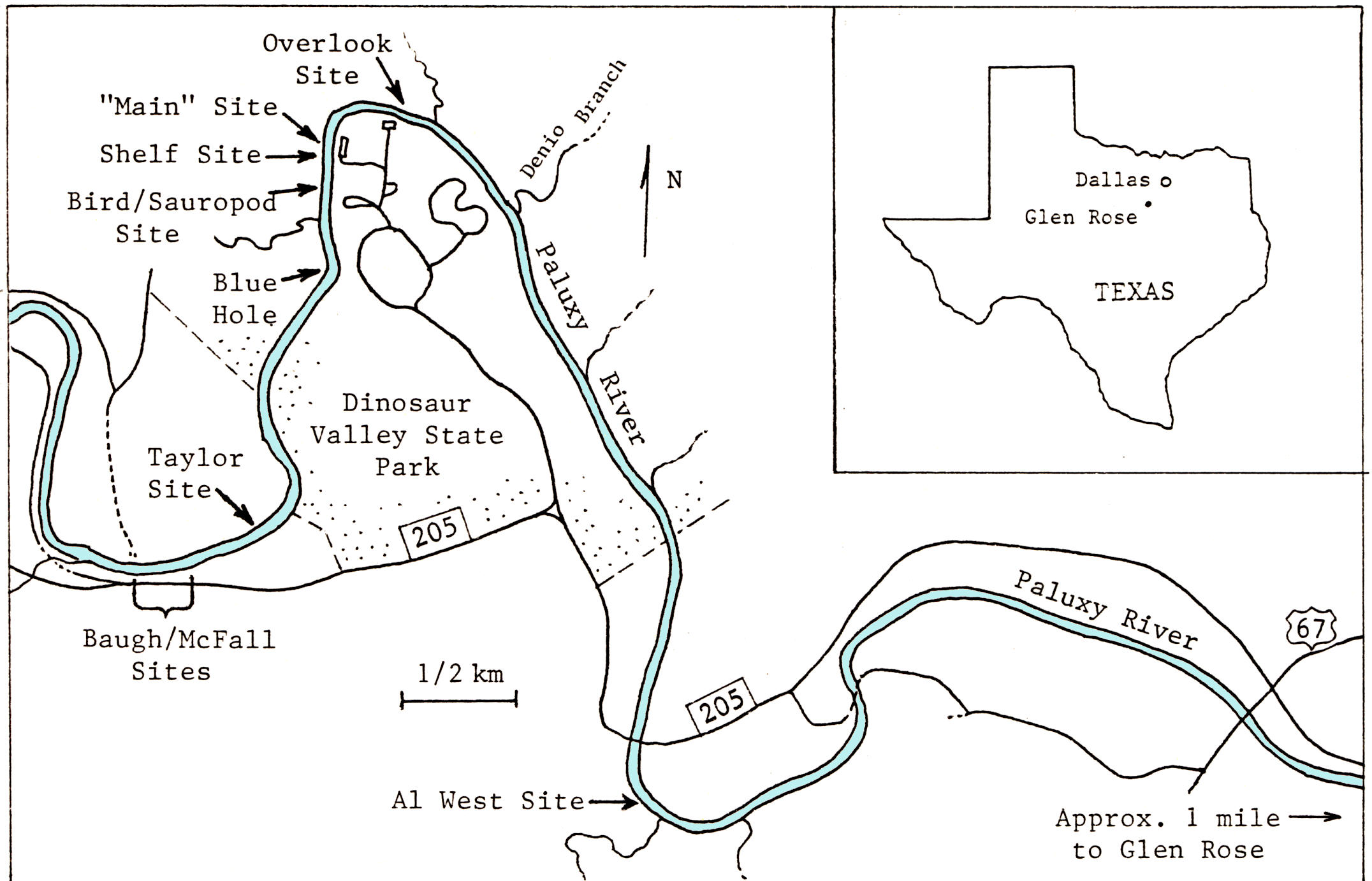

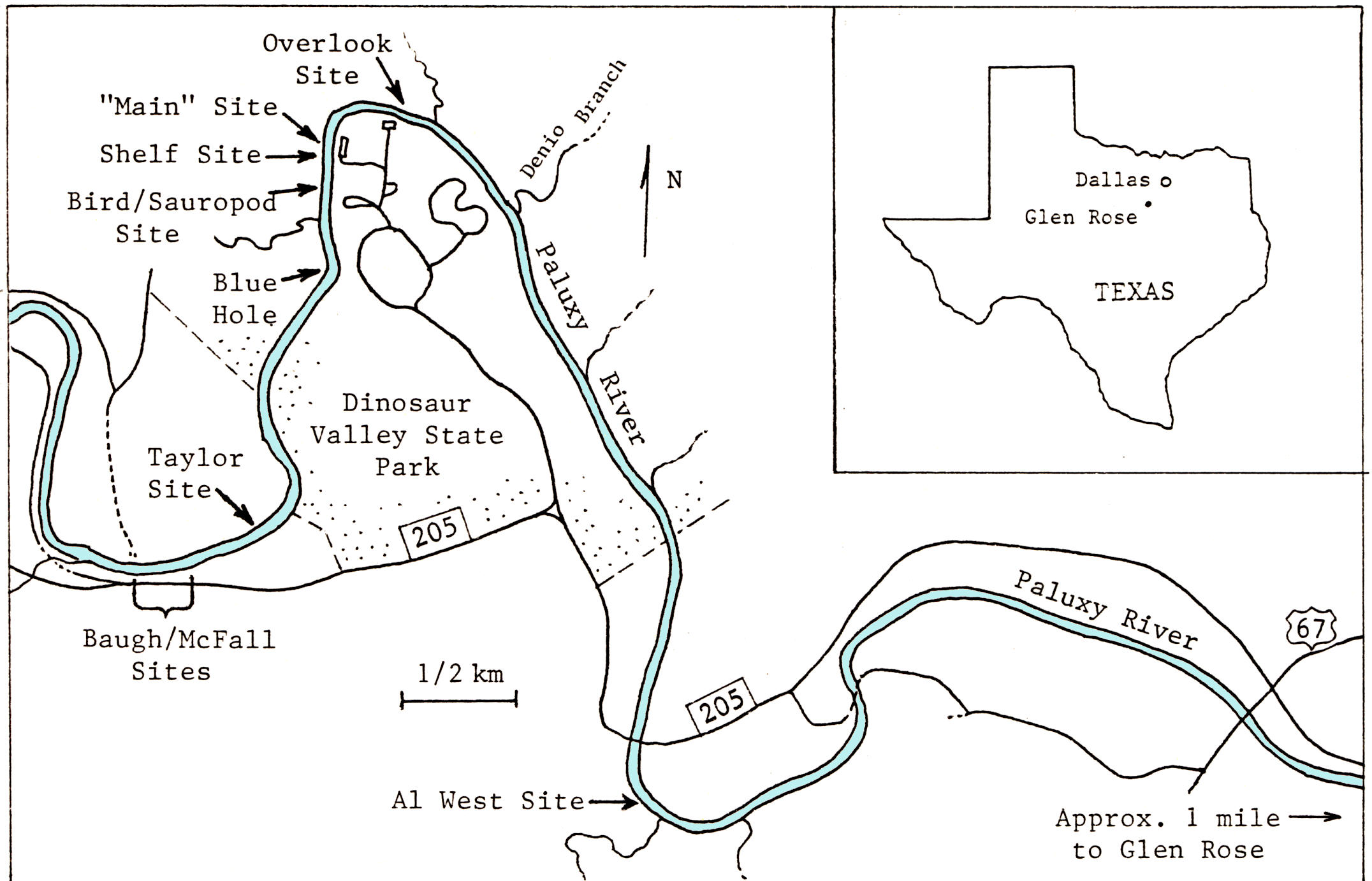

near Glen Rose, Somervell County, Texas. Glen Rose

is about 70 miles southwest of Dallas, Texas.

This on-line version of the paper is part of Kuban's Paluxy website at http://paleo.cc/paluxy.htm

Numerous elongate dinosaur tracks with apparent metatarsal impressions occur in the Paluxy Riverbed, near Glen Rose, Texas. These tracks vary somewhat in size, shape, and clarity, but are typically 55 to 70 cm long (including the metatarsal segment), and 25 to 40 cm wide (across the digits). In many cases the digit impressions on such tracks are indistinct, due to mud collapse, erosion, or a combination of factors--causing some to resemble giant human footprints, for which they have been mistaken by some creationists and local residents.

|

|

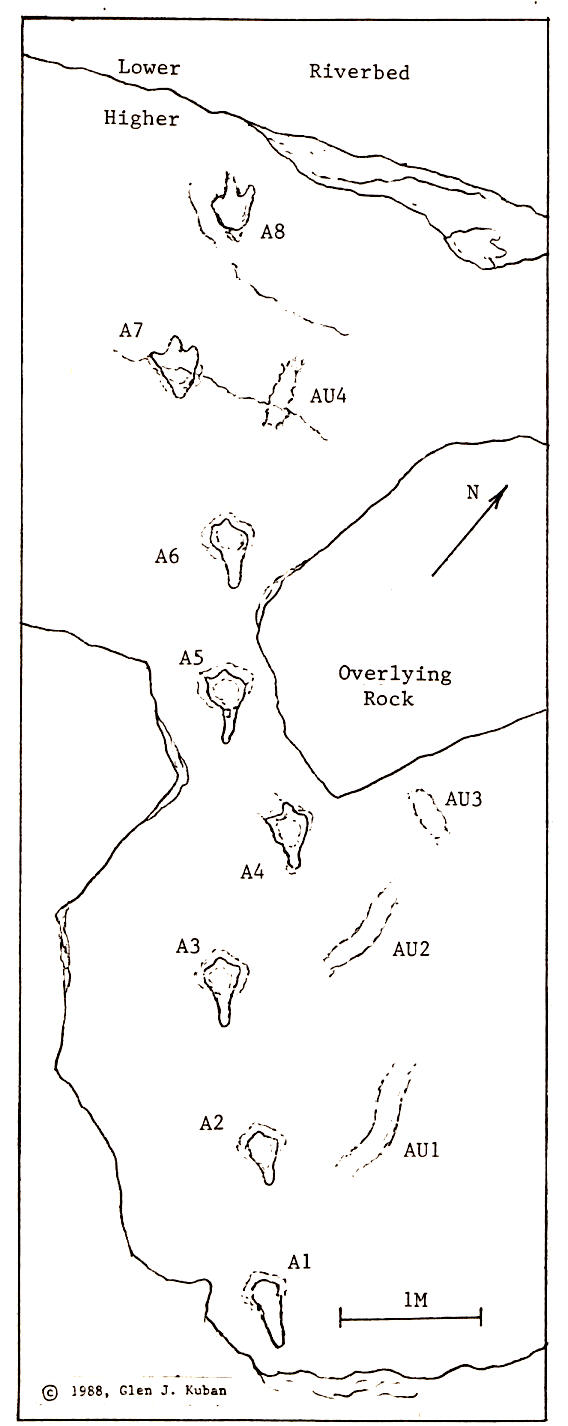

Figure 1.Locations of the relevant track sites near Glen Rose, Somervell County, Texas. Glen Rose is about 70 miles southwest of Dallas, Texas. |

| Figure 3. The Alfred West Site (east side) |

|

|

|

Figure 4A. The IIW Trail on the Al West Site. Track IIW13 is at the bottom. |

Figure 4B. Track W2, showing elongate, human-like shape, evidently due to metatarsal impression and mud collapse. |

Trail W occurs in an area of the site that is usually dry in summer, and where the rock surface is very coarse. The trackway includes both elongate and nonelongate forms alternating irregularly, with considerable variation in pace lengths and individual print features. Shorter pace lengths (less than 115 cm) predominate, however, some of the longer paces may be due to missing tracks (for example, between tracks W9 and 10 a print may be unrecorded, or may have been marred by IIW1, or may be under the bank). The elongate prints in trail W average 55-65 cm in length; the nonelongate ones, 35-40 cm. The digit marks on most elongate tracks in Trail W are indistinct, evidently due to mud collapse (slumping of mud back into the depressions), and later erosion. Note the superficially manlike shape of W2 (Fig. 4). Track W8 shows the outside digit (IV) more pronounced than the others--a common feature of elongate tracks in Glen Rose.

|

|

|

Figure 5A. The IIW Trail on the Al West Site. Track IIW10 at bottom. |

Figure 5B. Track IIW10. Tape measure at left is in inches. |

|

|

| Figure 5C. Track IIW13, a well preserved metatarsal track. |

Figure 5D. Track IIW14, a metatarsal track with mud-collapsed digits. |

Trail IIW (Figure 5) shows fairly long and consistent pace

lengths (114-156 cm) relative to track size, and fairly large

pace angles (140-160 degrees). All but one of the prints in

Trail IIW (Figure 5) are elongate, but they are slightly smaller

than the elongate prints in Trail W (comparing corresponding

areas of the prints). Many are indistinct, but a few are fairly

well-preserved. Track IIW2 shows digits splayed at a very wide

angle (about 140 degrees total divarication). Most other elongate

tracks in Glen Rose also show wide, but less extreme,

splaying--typically 75-90 degrees total divarication. Several

tracks in Trail IIW2 (and others in Glen Rose) show a narrow

and/or raised area between the ball and heel areas, which might

indicate a metatarsal "arch."

|

|

|

Figure 6. A (top photo). Track IV W2, a mud- collapsed metatarsal dinosaur track with a somewhat human-like shape, occurring in the same trail with more obviously dinosaurian tracks, such as track IV W2. B (bottom photo). Track IV W2 |

Trail IIIW is represented by a single metatarsal track near the broken north edge of the track layer, but originally may have been connected to Trail IVW. Trail IVW contains several deep elongate tracks with very indistinct (largely mud collapsed) digits, and one non-elongate track with three clear digit impressions (Fig. 6). This trail progresses into a very pock-marked area of the site. Trail VW contains only elongate tracks, some of which are very deep and distorted, and others of which are less deep and better preserved. Trails VIW and VIIW consist of several elongate tracks of variable clarity, but most show some indications of individual digits. Trail VIIIW is comprised of two well pre-served metatarsal tracks, with a large pace (224 cm). Trail IXW begins with two elongate tracks near the SE bank, then apparently becomes a digitigrade trail (the progression is ambiguous, since some of the tracks are indistinct).

Three Y-shaped depressions (U1, U2, U3) near Trail T are interpreted as possible tail marks. Each is situated about a half-meter from the midline of the trackway. The largest (U1) is about 65 cm across the longest dimension of the mark (Fig. 7). The Y-shape may be due to a double contact of a portion of the tail. Another small Y-shaped mark (U4) occurs in line with indistinct digitigrade tracks east of Trail VIW. Near U4 is an essentially straight elongate depression about 1 m long, and 8-13 cm wide. An apparent mud push-up on the wider end of the depression suggests that it may be a foot slide, but since no digit marks are visible, it alternatively may be a tail mark. An unusually large trace of unknown origin is situated between tracks T0 and IIT3; this is an oblong, shallow, smooth-bottomed depression about 80 cm wide and 3 m long.

|

|

Figure 8. Eastern section of Baugh/McFall ledge, containing a trail of tridactyl tracks with partial metatarsal impressions, and some indistinct elongate marks (AU1-AU4) possibly made by the dinosaur's tail or other body part. |

|

|

Figure 9. A. Trail A on the Baugh/McFall Ledge (compare map, Figure 8). The oblong mark below the black plaque at the left is marking AU4, shown close up in Figure 9C. |

Other subsites along the Baugh/McFall Ledge have been excavated since 1982 by teams of creationists led by Carl Baugh, who claims to have found over 50 "man tracks" there. These sites were reviewed by a team of four mainstream scientists (hereafter referred to as the "C/E team") who refuted the "man track" claims (Cole and Godfrey, 1985), but offered a few questionable interpretations of their own (discussed below). I began studying the Baugh sites in 1982, and in subsequent collaboration with Ron Hastings (a C/E team member), constructed detailed site maps.

The alleged human tracks on the Baugh sites involved several

phenomena. Some were posterior extensions on definite dinosaur

tracks, which Baugh interpreted as human tracks overlapping

dinosaur tracks (Figs. 8, 9B). The extensions vary in length, but

generally are smaller and narrower than those on the Al West

Site. The extensions were interpreted by the C/E team as hallux

marks, but the blunt ends and direct posterior positions suggests

they are more likely partial metatarsal impressions. Other

elongate tracks occur on other areas of the ledge; most showed longer

and more robust metatarsal segments (Fig. 10).

|

|

|

|

Figure 10A. A trail on the Baugh- McFall Ledge including tracks with robust metatarsal impressions and others with little or no metatarsal impression. |

Figure 10B. A trail on the Baugh- McFall Ledge including tracks with robust metatarsal impressions; others with little or no metatarsal impression. |

Figure 11A. Trail with metatarsal track showing mud collapsed digits, located on east side of Dinosaur Valley State Park. |

Other alleged "man tracks" on the Baugh sites included

shallow, indistinct elongate marks near, but not in line with,

dinosaur trackways. These marks, which are often slightly curved,

are generally situated about 0.5 m from the trackway midline

(Figs. 8, 9A, 9C). Some were interpreted by the C/E team as

tridactyl footprints whose side digits were poorly preserved, but

the marks are not in stride with other tracks, and show no

evidence of side digits. It seems more plausible that the marks

were made by another part of the dinosaurs's body, such as the

tail, or possibly the snout or manus (the latter two possibly

during food foraging). It is also possible that some of these

marks may be plant impressions (recently a branch was found in

such a position), or accidental gouges from excavation machinery.

Also identified by Baugh as "man tracks" were some vague, shallow depressions that appeared to be natural irregularities or erosional features on the rock surface. Some Thalassinoides burrows also were claimed by Baugh to be human "toes," and one abnormally-shaped "giant track" (over 60 cm long) was merely a carving in the firm marl that overlies the track surface.

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 12. A & B. Possible Tail impressions at the Main Site, Dinosaur Valley State Park |

Tail marks are rare in the park, but two possible tail marks occur near the "main" tourist area in the north-west portion of the park. One of these marks is a pronounced, curved impression about 1.5 m long and 10-15 cm wide (Fig. 12A). Overhanging the depression is what appears to be a ridge of mud pushed up by the tail, which partially slumped back into the depression. Along the bottom of the impression are shallow, parallel striations. Several tridactyl tracks and one sauropod manus/pes set are nearby, but it is difficult to determine which trackway, if any, is associated with the curved mark. Another possible trail mark (Fig. 12B) which occurs nearby is fairly straight, about 3.7 m long, and is straddled by two bipedal trackways. Overlapping the apparent tail drag is a footprint of one of these dinosaurs as well as a print of a third individual. Some shallow elongate grooves behind some sauropod pes tracks near Roland Bird's quarry site were interpreted by Fields (1980) as tail drags, but they are indistinct, and may be toe drags or river scours.

The "Shelf Site" in Dinosaur Valley State Park, situated above the "main track layer," was often claimed by creationists to contain many "man tracks." However, all the depressions appear to be erosional markings, involving river scouring, karst dissolution, and weathering. None exhibit clear human features (Figure 13).

| Figure 14. The Taylor Site (main section), based on field work between 1980 and 1985. Track outlines indicate boundaries of color distinctions and/orrelief differences from surrounding substrate. The north bank of the Paluxy River occurs just past the top of the map. Additional tracks occur ourside the map borders, including the Ryals Trail (Fig. 15). |

Until the 1980's little study of the Taylor Site was made by noncreationists, apparently due in part to inaccessibility (the site is usually under water), and reluctance to treat the "man track" claims seriously. Some authors suggested the "man tracks" were erosion marks or carvings; others attributed them to single digit impressions of bipedal dinosaurs, or mud-collapsed typical (digitigrade) dinosaur tracks. I have been studying the Taylor Site since 1980, and have concluded that the "man tracks" and other elongate tracks there are plantigrade dinosaur tracks.

| Figure 15. Ryals Trail section of the Taylor Site. This section occurs just east of the area shown in Figure 14. Intersecting the Ryals (RY) Trail is the IIDW Trail, a long sequence of metatarsal tracks that traverses the entire riverbed and intersects the Taylor Trail near the north bank (compare Fig. 14). |

The most renowned "man" trail on the site is the Taylor (IIS) Trail, containing 15 known tracks, most of which are large and elongate. The gait pattern is irregular, including some short, wide paces, and other long, narrow paces; most other trails on the site show more regular gait patterns (Figs. 14, 15). Most tracks in the Taylor Trail (Fig. 14, 16) show a prominent metatarsal segment, slight mud push-ups along the sides, and a shallow anterior end with indications of a tridactyl pattern (often accentuated by color distinctions, explained below).

|

|

| Figure 16. A. High overhead view of the main section of the Taylor Site, facing southwest (1984). The Taylor (IIS) Trail proceeds from bottom-center to upper left. Other trails are visible in background (compare map, Fig. 14). | Figure 16. C. Taylor Trail track IIS,+3. This track showed an unusually rounded anterior end (possibly due to the way the mud was pushed up by the middle digit), but still showed a tridactyl pattern. |

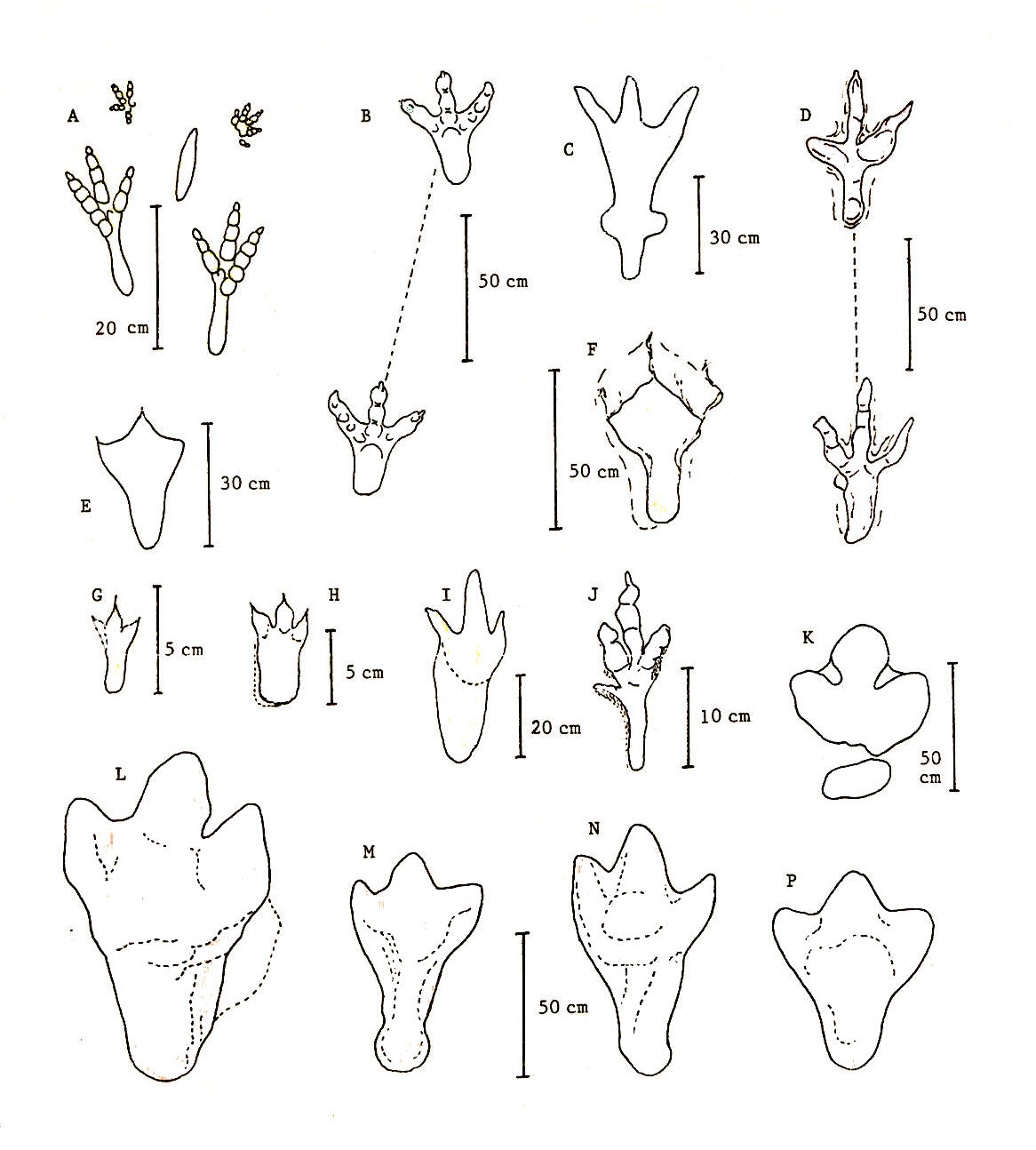

Apparent metatarsal dinosaur tracks in striding trails have been found at several sites besides those in Glen Rose; some of these are discussed below, with examples shown in Figure 17.

| Figure 17. Elongate (metatarsal) dinosaur tracks outside Glen Rose, Texas. |

Trails of elongate tracks similar to those in Glen Rose have been observed at a Cretaceous site in Bandera County, Texas, by James Farlow (personal communication, 1986), and by me and others at another Cretaceous site in Comal County, Texas, although the tracks at both sites are indistinct (Fig. 17F).

Many large, blunt-toed tracks with apparent metatarsal impressions have been found in Cretaceous coal mine roofs in Utah (Figs. 17L-17P); one such track was over 130 cm long (Strevell, 1940). At the opposite end of the size spectrum, Thulborn and Wade (1984) described tiny (5-10 cm long) tridactyl tracks of the ichnogenus Skartopus at a mid-Cretaceous Australian site and indicated that a few Skartopus tracks possessed what appeared to be metapodial impressions (Fig. 17H). Thulborn and Wade noted that metapodial Skartopus tracks usually occur as isolated prints, although one series of three such tracks was found.

Several trails of elongate dinosaur tracks occur at a Lower Cretaceous site at Clayton Lake State Park, New Mexico (Gillette and Thomas, 1985). Gillette and Thomas interpreted some of these tracks as webbed-toed theropod tracks with metatarsal pads (Fig. 17E), and others as ornithopod tracks whose elongation was due to slippage in the mud.

Striding trails of tridactyl tracks with widely splayed digits and posterior extensions (Fig. 17B) were reported from sites in South America by Giuseppe Leonardi (1979), who tentatively interpreted them as plantigrade ornithopod tracks, although I consider them theropod tracks. Similar tracks (Fig. 17D) have been reported by Shinobu Ishigaki at a Jurassic site in Morocco (James Farlow, personal correspondence, 1986).

Interesting elongate tracks were reported from a Late Cretaceous site in Spain (Brancas et al, 1979). Near the track heels are curious lateral protrusions that may be "ankle" impressions (Fig. 17C).

In many cases the length, shape, and position of the long posterior segment of elongate tracks rules out a hallux interpretation. A simple foot-slide explanation is also incompatible with the shape and details of many elongate prints, especially those with "pinched-in" centers. Further, although foot slides do occur, they generally show significant distortions, such as a mud "pile-up" at the anterior; whereas most mud push-ups, where present on elongate tracks in Glen Rose, usually are more pronounced at the sides than the front of the track. The above features also confirm that most elongate tracks in Glen Rose are not simply eroded digitigrade tracks, especially since many are oriented contrary to river flow.

The idea that the posterior extensions may have been a thick "metatarsal pad" supporting an essentially digitigrade foot, as in elephants (or as suggested for an isolated Hadrosaur track by Langston, 1960), is inconsistent with the length and narrowness of many of the posterior extensions.

Roland Bird, who examined a limited number of elongate dinosaur tracks during his well-known sauropod studies in Glen Rose, proposed that such tracks may have been made when a dinosaur pressed its toes together upon withdrawing its foot from soft mud (Bird, 1985). However, this would suggest considerable distortion within the track, especially at the back, which is inconsistent with appearance of the better-preserved elongate tracks, especially those which show a narrowing in the "arch" region, and a rounded tarsal element at the posterior.

A popular hypothesis in the past for elongate tracks in Glen Rose was that they were middle digit impressions. This concept has several variations, one of which holds that only the middle digit might register if the substrate were firm, or if the track were an overtrack or undertrack. However, on most elongate tracks one can see at least some indications of all three digits, and these digit marks are consistently located at the front of the track, not emanating from the back and sides as would be the case if the body of the print were a middle digit. Further, on well preserved Glen Rose tracks the middle digit is about the same depth as the side digits.

|

|

Figure 18. A. A typical tridactyl dinosaur track (left) and the common shape resulting from mud collapse (right). B. A typical metatarsal dinosaur track (left) and the common result of mud collapse: an elongate depression that somewhat resembles a large human footprint (right). C. (Left) A metararsal dinosaur track may also be subdued due to erosion, locomotion on a firm substrate, ghost impressions (over- and uner-tracks), infilling, or a combination of factors, resulting in an elongate depression the roughly resembles a "giant man track." C (Right). If a metatarsal dinosaur track is first mud-collapsed, then less erosion is needed to foster a humanlike shape, and even the size of the depression may be close to that of a normal human print." |

Although the above evidences establish that many elongate tracks are metatarsal tracks (recording at least part of the metatarsus), whether they are also "plantigrade" tracks raises a question of terminology. Although some workers may define a "plantigrade" track as one that records any of the metatarsus, others (including me) may wish to restrict the term "plantigrade" to tracks exhibiting complete or nearly complete metatarsal impressions oriented in a largely horizontal manner, or require that several such tracks occur in succession. In any case, some trails in Glen Rose and elsewhere do show several full metatarsal tracks in sequence, and therefore, even by strict definition, may be considered "plantigrade" or at least "quasi-plantigrade," the latter allowing for variations and uncertainties in the behaviors and environmental factors involved (discussed below).

A soft and/or slippery sediment may have encouraged a dinosaur to lower its metatarsi onto the sediment in order to gain firmer footing. However, if this were a primary cause of metatarsal tracks, one might expect such prints to show relatively short paces, reflecting more cautious steps. In contrast, many elongate tracks in Glen Rose have moderate to long paces and pace angles. A few elongate trackways do show erratic gait patterns that might be construed as evidence that the trackmaker was contending with a slippery substrate, but similar gait patterns can be seen in some non-elongate trackways as well.

|

|

Figure 19. A. A typical bipedal dinosaur walking in a digitigrade mode. B, C. Possible postures assumed by bipedal dinosaurs during plantigrade locomotion. |

Perhaps the most plausible explanation, however, is that plantigrade tracks may have been made occasionally by a variety of bipedal dinosaurs whenever they walked low to the ground, which would decrease the angle between the metatarsus and the substrate (Fig. 19B). A low posture may have been assumed whenever a dinosaur foraged in mud flats or shallow water for small food items (such as molluscs, insects, crustaceans, amphibians, fish, eggs, or edible plant material); when stalking larger prey, or when approaching other dinosaurs.

That any pathology was involved in causing most metatarsal tracks seems unlikely in view of the relatively efficient stride patterns in most elongate trackways, and the great abundance of metatarsal tracks in some areas, such as Glen Rose.

It may be that some bipedal dinosaurs may have had leg anatomies more suited to plantigrady than others, although it is unlikely that any were obligatory plantigrade walkers, since most trails with elongate tracks also contain some non-elongate tracks. However, determining with certainty what factor(s) caused such tracks is difficult, especially since more than one of the factors discussed above (and others) may have acted singly or in combination to foster metatarsal impressions.

Most metatarsal tracks near Glen Rose appear to have been made by moderate sized theropods; however, the variety of elongate tracks in Glen Rose suggests that more than one species in that area made them, and the additional varieties of metatarsal tracks found in other areas further suggests that plantigrade or quasi- plantigrade walking may have been a fairly widespread (though intermittent) behavior among both theropods and ornithopods.

I would like to acknowledge the field assistance of Ron J. Hastings, Tim Bartholomew and Alfred West, and students Dan Hastings, Marco Bonneti, Mike White, Alan Dougherty, Brian Sargent, and Tim Smith. I also would like to thank James O. Farlow for providing helpful comments and literature references.

Alexander, R. McN., 1976. Estimates of speeds of dinosaurs. Nature, 261:129-130.

Ambroggi, R., and A. F. de Lapparent, 1954. Les empreintes de pas fossils du maestrichtien d'Agadir. Morocco Service Geologique, 10:43-57.

Beierle, Fred, 1977. Man, Dinosaurs, and History. Perfect Printing, 67 pages.

Brancas, Rafael, Jorge Blaschke, and Julio Martinez, 1979. Huellas de dinosaurios en Enciso. Unidad de Cultura de la Excma, 2:74-78.

Bird, Roland T., 1985. Bones for Barnum Brown. Edited by V. T. Schreiber. Texas Christian University Press, 215.

Cole, John, and Laurie Godfrey, eds., 1985. The Paluxy River footprint mystery--solved. Creation/evolution, 5(1). (With articles by Cole, Godfrey, S. Schafersman, and R. Hastings).

Fields, Wilbur, 1980. Paluxy River explorations. Self published by Wilbur Fields, Joplin, Mo., 48 pages.

Gillette, David D., and David A. Thomas, 1985. Dinosaur tracks in the Dakota Formation (Aptian-Albian) at Clayton Lake State Park, Union County, New Mexico. New Mexico Geological Society Guidebook, 36th Field Conference, Santa Rosa, 283-288.

Hitchcock, Edward, 1948. The fossil footmarks of the United States and the animals that made them. Transactions of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Vol. 3, 128 pages.

Leonardi, Giuseppe, 1979. Nota preliminar sobre seis pistas de dinossauros Ornithischia da bacia do Rio do Peixe, em Sousa, Paraiba, Brasil. Academia Brasileira de Ciencias, 51(3):501-516.

Langston, Wann, Jr., 1960. A Hadrosaurian Ichnite. Canada National Museum of Natural History Paper, 4:1-9.

Langston, Wann, Jr., 1979. Lower Cretaceous dinosaur tracks near Glen Rose, Texas. In: Lower Cretaceous shallow marine environments in the Glen Rose Formation. American Association of Stratigraphic Palynologists. Field Trip Guide 12. Annual Meeting, 39-55.

Lull, Richard S., 1953. Triassic life of the Connecticut Valley. Connecticut Geological and Natural History Survey, Bulletin 81.

Morris, John D., 1980. Tracking those incredible dinosaurs and the people who knew them. Creation Life Publishers, 240 pages.

Morris, John D., 1986. The Paluxy River Mystery. Impact. 15(1).

Neufeld, Berney, 1975. Dinosaur tracks and giant men. Origins, 2(10):64-76.

Olsen, Paul E., 1986. How did the small Ornithischian trackmaker of Anomoepus walk? 1st International Symposium on Dinosaur Tracks, Abstracts with Program, 21.

Shuonan, Zhen, Li Jianjun, and Zhen Baiming, 1983. Dinosaur footprints of Yuechi, Sichuan. Memoirs of Beijing Natural History Museum 25:1-20.

Strevell, Charles N., 1940. Story of the Strevell Museum, Salt Lake City Board of Education, 7-15.

Taylor, Stanley E., 1971. The Mystery Tracks in Dinosaur Valley. Bible-Science Newsletter. 9(4): 1-7.

Taylor, Stanley E., 1973. Footprints in stone (film). Films for Christ Association.

Taylor, Paul S., 1986. Footprints in stone: the current situation. Origins Research, 9(1): 15.

Thompson, Ida, 1982. The Audubon guide to North American fossils, plate 472.

Thulborn, Richard A., and Wade, Mary, 1984. Dinosaur trackways in the Winton Formation (Mid Cretaceous) of Queensland. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, 21(2):413-517.